As I was rewatching Simon Amstell's brilliantly introspective and very funny Set Free, an account of his journey through trauma healing, experimentation with open relationships and psychedelics, it occurred to me that the show captures something deep about the politics of our age.

It would be accurate to describe Amstell as someone on the left - vegan, opposed to an economic system that forces us to sell our labour in order to survive ("I'm so annoyed that I still have to earn money!") and deeply worried about the environmental catastrophe that we are bringing about. But this label "left" feels a little too 19th century for a comedian with a Netlfix special.

It's become a bit of a cliché to argue that "left and right" no longer meaningfully describe today's political spectrum. Major Parties are changing their identities and orientation. Up is down, left is right, the conservatives have become radicals, and the progressives have become defenders of the status quo. There is even such a thing called "radical centrism". This flux, this coexistence of opposites within each thing was one of the reasons Plato condemned the world of appearances as illusory (the shadows inside Plato's cave).

But Amstell's anecdotes about the insights he gained along the way and his renewed perspective on the world (was comedy always this philosophical?) made me think that there is perhaps something deeper behind this flickering of political labels. Behind what seem like ephemeral political divisions lies a philosophical disagreement about the fundamental nature of reality, and both sides have it wrong.

All is One?

Amstell's show is not really about politics. The focus of the stories he tells is about his process (ok, "journey") of coming to terms with himself, his own body, his desires, his status anxiety, his relationship to his childhood and his parents.

Psychedelics have been having a moment (my former colleague Ricky Williamson thinks their increased use might usher in a new age of moral thinking), and Amstell, like many other creative types, fuelled his process of self-acceptance with (alongside more conventional methods like therapy) drugs.

One way to make sense of the salient political division of our times is between those who see boundaries as dissolvable and advocate for unity, and those who valorise boundaries and think that their dissolution leads to a loss of meaning, anarchy and chaos.

His first experiment takes place in a South American jungle, taking ayahuasca in a ritualistic context led by a shaman. This lead Amstell to the thought: "I don't feel separate to nature, I am nature."

The second experiment takes place in a more urban environment, a party with other creative types, and the drug of choice there is MDMA . He describes the thoughts the drugs induced in him as follows: "All the boundaries are dissolving, all the conventions all the boundaries of my own personality, of society, I thought there were no boundaries anymore."

These insights are quite typical for those who take psychedelics. At the right amounts these drugs seem to have an ability to dissolve the ego, to make you see the world as one big whole, a unity, of which you are not just a part of, but one with.

This idea, that everything is one, goes way back, at least as far as the Ancient Greek philosopher Parmenides. For him, as for Plato (who was deeply influenced by Parmenides) the world as we experience it, full of many different things and constant change, is full of contradictions and therefore a mere appearance, an illusion. The truth about reality is that all is one: Being. Being is all that exists, Parmenides argued, and Being is one thing, as everything that is not-Being does not exist. This idea that everything that exists is ultimately the one same substance is repeated in different versions by later Western philosophers and given the name “monism”. The same thought is encountered in other philosophical traditions, most notably Buddhism.

Bust of Parmenides, source: Wikipedia

So, what does all this have to do with politics? Well, one way to make sense of the salient political division of our times is between those who see boundaries as dissolvable and advocate for unity, and those who valorise boundaries and think that their dissolution leads to a loss of meaning, anarchy and chaos.

The Politics of Boundaries

The new right, for lack of a more inclusive term, does seem to be rather obsessed with boundaries. To begin with, the new right is very hung up on the physical boundaries of countries: borders. "Securing our borders" was one of Trump's first executive orders in 2025. An open hostility towards immigration is not exclusive to Trump of course. The same can be said about Farage in the UK, Orban in Hungry, Meloni in Italy, and others in who belong to the same political space.

The focus on immigration as something to be combated divides the word into different parts, “nation states” and it separates people into "communities" and nationalities. These boundaries are not seen as metaphysically arbitrary, but as essential, defining the nature of the things and people that occupy different sides of them.

This preoccupation with national borders and with protecting the “community” against outsiders is reminiscent of the Open vs Closed societies framing of Karl Popper in his1945 book The Open Society and its Enemies. For Popper “The closed society is tribal or collectivist.” Henri Bergson also used this framework of open vs closed society, defining the latter as "one whose members hold together, caring nothing for the rest of humanity, on the alert for attack or defence, bound, in fact, to a perpetual readiness for battle." This tribalism of “us against the rest of humanity” lies at the polar opposite of the more universalist/monist sensibility of something like the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights which sees all human being as sharing not just the same nature, but having the same legal status when it comes to the fundamental requirements for a dignified human life

This political focus on boundaries is not true just of the physical borders of countries. One of the most divisive issues of our day is the status of transgender people. A political battle has been taking place between those who see the genders as well-defined, separate, and concrete categories, and those who see the boundary between men and women as fluid and permeable at a societal level. In a separate discussion taking place in the so-called “manosphere” there are those aiming to revive robust conceptions of men's and women's natures (and roles) and upholding rigid divides between the two genders. Meanwhile the other side sees gender as a social construct that can be remoulded to fit the needs and desires of those inhabiting it.

Once you start thinking of our political divides in terms of this "unity vs difference" framework, you see it everywhere. How we think of our relationship to the environment and to other animals is another one of those test cases for our politics. The environmental movement has not only been trying to get us to care about climate change and the general health of the environment - it’s been on a mission to shift the Enlightenment mindset of seeing ourselves as separate from nature. Once we start seeing ourselves not as standing outside of nature, but as nature, framing our natural environment as something to be instrumentalised and exploited for financial gain stops seeming like such a great idea.

The vegan movement has similarly been in the business of erasing the species borders we have erected. Philosophers also played their part in this, perhaps most notably Descartes who saw animals as machines lacking minds. But scientific and philosophical developments have increasingly made it harder to identify what separates us from other animals (language, technology, reasoning?). One thing that has become impossible to deny is that what we share with other animals - at the very least other mammals, fish, and birds - is our ability to suffer: to feel fear, anxiety, and pain.

A more ambitious way to resolve the tension between unity and difference is to try to overcome the opposition altogether.

The philosophical foundations behind this politics of boundaries might be a little murkier to identify, but they are there. A picture of reality that sees it comprised of a metaphysical hierarchy – distinct levels of “Being” – can already be found in Aristotle. This image of reality translated into the human realm leads to a politics that is averse to egalitarianism, emphasises social hierarchy, and sees inequality as a natural outcome.

The focus on boundaries and difference as the way to conduct politics has also been explicitly endorsed by conservative intellectuals such as Carl Schmitt ("The political is founded on the friend/enemy distinction"), Roger Scruton ("A culture begins with boundaries, and only within boundaries can there be home, identity, and love"), and others.

Unity and Difference

Towards the end of his show, Amstell comes back to his opening diagnosis of the problem with everyone (including himself) needing to feel special. His experiences with psychedelic drugs and therapy gifted him the insight of metaphysical monism – all is one – “I didn’t need to feel special anymore because I felt connected. I am you. I am you. And the only problem I have in my life now is not being on MDMA!”

But Amstell is wrong here. If we went about our daily lives seeing everything as being the same, that would be a problem. We wouldn’t get very far if we couldn’t tell apart our shoes from our breakfast. And if I started treating every human with the same level of attention and love that I treat my son, I would quickly run out of time and resources to do anything at all. So even though the metaphysics and politics of borders are deeply unappealing to most progressives, a metaphysics and politics of unity come with their own issues.

Our political divisions are the result of understanding the metaphysics of unity and difference as an “either-or” choice.

One way to resolve the fact of both pictures of reality have pros and cons would be to oscillate between the two, depending on the context. This would be a pragmatist kind of solution. For example, when I’m conversing with another human being, even though we’re both members of the same species, that fact doesn’t really come into it. What I care about in the moment is their individuality: who they are, what they are saying to me, what it reveals about the way they see the world. The ways in which we are different is what’s relevant. Contrary, in a medical setting say, when a doctor is removing an appendix from a patient, what matters is our shared human physiology and differences about our psychology and character fade into irrelevance. But this oscillation doesn’t get us very far in politics where disagreements can be recast as arguments about whether the context calls for a politics of unity or difference. Should we treat immigrants as people with the same legal rights as us that just happened not to be born on this part of land? Or should we see them as outsiders, not belonging to our community and hence not entitled to the same protections our members enjoy?

Another, more ambitious way to resolve the tension between unity and difference is to try to overcome the opposition altogether.

As every student of Hegel is told, you can't really understand the preface to The Phenomenology of Spirit unless you have already understood the whole book, so don’t expect miracles here (I’m still trying to understand after doing a PhD on this stuff). In that preface, Hegel tries to distance himself from a contemporary of his, a philosopher named Shelling. Shelling was a monist of sorts, he believed in the “all is one” credo. All differences we observe, all the distinctions we draw, according to Shelling, ultimately collapse into identity; everything is ultimately the same: nature. Hegel was drawn to this idea too, but he believed it was too simplistic a picture of reality. Instead, he believed in preserving difference, even when acknowledging unity. “Identity-in-difference” is the philosophical slogan for this position. Reality for Hegel was ultimately a coherent whole, but that whole included difference – not everything that belongs to the whole is the same, and even when everything is seen as part of that whole, they still retain their distinct identity. What’s more, Hegel saw concepts like “unity” and “difference” not as opposites but as existing in a dialectic relationship with each other. Each concept, according to Hegel, only makes sense against the other, and in that sense unity contains difference, and difference contains unity.

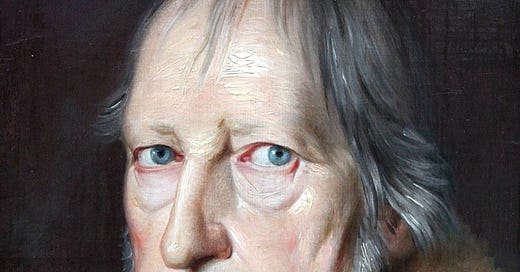

Portrait of Hegel by Jakob Schlesinger, source: Wikipedia

Hegel thought that many of the problems of philosophy and politics stem from the fact that human understanding operates in oppositions: freedom vs necessity, infinite vs finite, unity vs difference. He saw the task of philosophy as overcoming this framework of opposition, demonstrating that these seeming opposites could be brought together to form new ideas that contained both of them. Even though he never really uses this framework of “thesis – antithesis – synthesis”, this has become a standard way to begin to understand Hegel’s dialectic, showing how two seeming opposites could be brought together under one new concept.

Our political divisions are the result of understanding the metaphysics of unity and difference as an “either-or” choice. Perhaps a way out of the intellectual and political deadlock we are in would be to take a leaf out of Hegel’s philosophy and try to overcome this opposition, synthesising it into something new. A new politics beyond unity and difference, containing both.

…………

Thanks to Fay Schlesinger and Hugo Drochon for their comments on an earlier draft.